Water, Water, What To Do?

By Ronnie Hammond

November 3, 2022

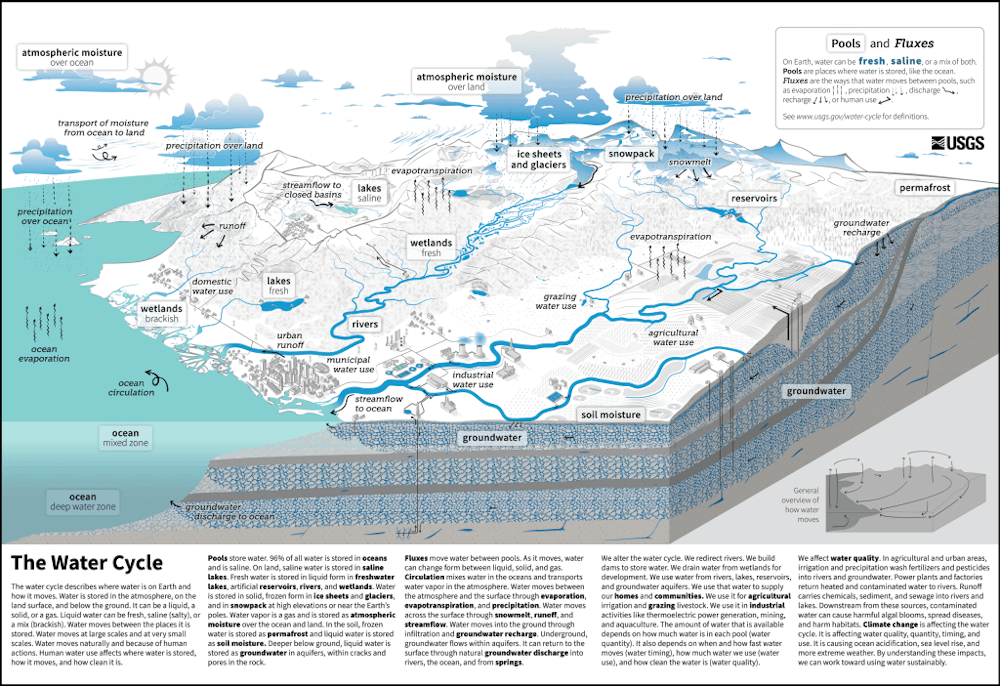

You may remember the “before times” as extremely normal. Human brains tend to put a rosy patina on the past, so maybe things weren’t so “extremely” normal after all. But compared to the “normally extreme” that’s coming, it’s probably going to seem that way. That was my take-away from the two keynote speakers at the California Department of Water Resources’ recent Drought To Flood Symposium [https://water.ca.gov/News/News-Releases/2022/Oct-22/DWR-Hosts-Drought-to-Flood-Symposium] held in mid-October.. To call my take-away an oversimplification is an understatement, to be sure. But the water cycle can get complicated pretty quickly, so a bit of simplicity may help us wrap our heads around it. The October 17, 2022 symposium was a discussion about building resiliency in the face of a bucking bronco of weather in the western US. Dr. F. Martin Ralph (Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes at UC San Diego Scripps Institution for Oceanography), and Dr. Daniel Swain (Institute of the Environment and Sustainability at UCLA) graphically described California’s current and projected water situation. They stated that there is not much of what we’ve come to think of as “normal” in our future. And while we are already living it, tighten your seat belts, because it’s going to be a bumpy ride of deeper drought and occasional floods, with no end of this journey in sight. When compared to the entire United States, California has a naturally more variable climate regime. Most of our precipitation has come from a relatively few number of storms. California’s bounty has relied on the snow pack from these winter storms, and subsequent snow melt through the growing season. When we get just enough water from “atmospheric river” storms (they’ve developed a scale, 1-5, that describes the intensity and duration of an atmospheric river), we have a decent water year; when we don’t get them, we have drought. When we get too much, we have floods. And not only would “normal” have enough storms, but they would be weaker (scale 1 & 2) storms. Stronger (scale 4 & 5) storms can also cause more damage. Climate models predict deeper droughts and fewer, but higher intensity, atmospheric river storms. Sound familiar? In the current drought, much of the state is now about a year behind in the precipitation that we “normally” would have received by now. Then add in warming temperatures, and you get more evaporation, thus an even greater need for water to feed the ecosystem and agricultural economy that we currently enjoy (or used to enjoy, before a lot of it burned up). The warming temperatures are a primary driver in the greater frequency of extremes. Dr. Daniel Swain pointed out that we haven’t seen a large change in average precipitation. This not a story of average precipitation, because there is no story there, and thinking about it is actually misleading about our current situation. This is the story of everything else – we have already seen a large increase in both drought and flood extremes – he called it whiplash. And more of that is in our future, and it’s pushing California’s water management infrastructure to the brink. The natural snowpack we’ve relied on is shrinking, the precipitation window is shrinking out of the shoulder seasons (spring and fall), and into fewer winter months. And when rain falls on snow, you get even higher intensity flooding. What to do? For DWR, they are beginning to use Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operations, which basically means using better weather prediction models and increasing flexibility of reservoir levels to store flood waters when they are predicted. For those of us living above the major reservoirs, this does not have much use. For producers in places like Sierra Valley, below Frenchman Reservoir; and Indian Valley below Antelope Lake this will have an impact. They also talked about a storm scenario called ArkStorm2.0. This model predicts the potential damage caused by a megaflood, a phenomenon coming to California about every 200 years (the last one being in 1862). The current prediction is for about $1 trillion in damages from the next megaflood. More accurate predictions of where the damage could occur may help with preparing. Other adaptations to this normally extreme include: ensuring that “hard” infrastructure, like levees, dams and urban flood conduits (like the Ditch in Chester) will perform as expected; and greatly expanding “soft” infrastructure like levee setbacks, river bypasses, and floodplain protection and restoration; as well potentially increasing underground flood pools (managing aquifer recharge), and informing the public and land use planners about our water cycle and where it’s heading, and plan accordingly. Just because that floodplain is nice and flat, doesn’t mean you should build on it. It’s called a floodplain for a reason. We’re in a drought – plan for a flood.

Featured Articles

Sierra Hardware Plans Extensive Repairs After Flood Damage →

December 8, 2025

Sierra Hardware faces extensive repairs after Thanksgiving flood damages store flooring and drywall.

Sheriff’s Office Accepts $60,000 Grant for New Search and Rescue Team →

December 2, 2025

Confusion Surrounds Release of the Plumas County Grand Jury’s Report →

December 4, 2025

WCB Considers Grant for Sierra Valley Tribal Land Purchase →

Updated November 22, 2025

Downieville Fire Auxiliary Hosts Annual “Holiday on Main” Event Saturday →

December 2, 2025